“Then the Lord rained on Sodom and Gomorrah sulfur and fire from the Lord out of heaven.”

“Lot’s wife looked back, and she became a pillar of salt.”

— Genesis 19:24–26 (KJV)

For centuries, millions of believers have read these verses as sacred history: two cities incinerated by divine wrath, a woman frozen mid-glance as a salt column, an eternal warning against sin. The imagery is vivid, iconic, and invested with moral force. It’s a spectacle of cosmic justice.

Despite decades of seekers digging into the past to substantiate the stories from antiquity, none of the claims holds up under scrutiny.

Geological and Archaeological Evidence against Airburst Hypothesis

Tall el-Hammam, a Bronze Age city in the southern Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea, was proposed in 2021 to have been destroyed by a cosmic airburst around 1650 BCE. The paper by Bunch et al. (Scientific Reports, 2021) claimed evidence based on microscopic “shocked quartz,” melted building materials, and anomalous concentrations of platinum and iridium, suggesting a Tunguska-like atmospheric explosion.

The excavation at Numeira revealed remarkably well-preserved remains—including textiles, seeds, and clusters of grapes—showing the city was destroyed by an intense fire, not by brimstone or divine intervention.

Subsequent analyses have rejected these claims. Jaret and Harris (2022, Scientific Reports) conducted a detailed re-examination of the mineralogical and geochemical evidence. They found that the purported shock features in quartz grains were not consistent with recognized shock-metamorphic criteria and that the geochemical anomalies cited could not be reliably measured with the methods used. They further demonstrated that the high-temperature melt materials could be explained by terrestrial processes, including urban fires, pottery kilns, and metallurgical activity.

Physical modeling also contradicts the airburst hypothesis. Boslough and Bruno (2025, Scientific Reports) showed that the pressures, heat, and wind speeds required to produce the destruction described by Bunch et al. were physically implausible given known airburst dynamics, including analogs like the Tunguska and Chelyabinsk events. Their work confirms that the purported effects cannot be reproduced by any reasonable cosmic explosion scenario.

Reflecting these critical evaluations, Scientific Reports formally retracted the original 2021 paper in April 2025, citing methodological flaws, unsupported conclusions, and insufficient evidence to substantiate an extraterrestrial event.

The melted pottery and glass found at Tall el-Hammam are the result of intense city fires, not a meteor or cosmic impact.

The scientific consensus is clear: there is no credible mineralogical, geochemical, or physical evidence that Tall el-Hammam was destroyed by a cosmic airburst or meteor. The destruction layer at the site is best explained by terrestrial causes, such as intense urban fire, warfare, or seismic activity typical of the Middle Bronze Age. Any claims of an airburst event are unsupported and not accepted by the scientific community.

Salt Pillars Exist Naturally—No Miraculous Transformation Needed

Some proponents point to the “salt pillars” near Mount Sodom or along the Dead Sea as physical proof of Lot’s wife turned to salt. However, these formations are entirely natural geological features, not petrified humans.

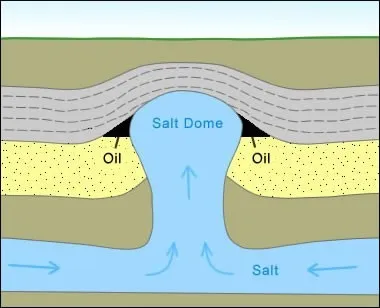

Mount Sodom is composed largely of salt diapirs, massive blocks of halite that have been slowly forced upward through overlying sedimentary layers by tectonic pressures over millions of years. These towering halite columns are shaped by a combination of uplift, erosion, and fracturing—processes entirely explainable through geology. Rainfall, flash floods, and wind erosion gradually sculpt the salt into dramatic pillars, spires, and cliffs.

The origin of these salt formations can be traced back to the Messinian Salinity Crisis, roughly 5 to 6 million years ago, when the Mediterranean Sea nearly dried up due to the temporary closure of the Strait of Gibraltar. As the water receded, massive evaporite deposits—including halite, gypsum, and other salts—accumulated across the basin. Later tectonic activity associated with the Dead Sea Transform Fault uplifted and deformed these deposits, producing the diapirs we see today. Over geological time, seismic activity and ongoing salt creep continue to reshape these formations, creating pillars and jagged outcrops that can resemble the dramatic imagery described in Genesis.

The “pillar of salt” motif in the biblical story is thus more plausibly symbolic than literal, representing moral caution or fixation on the past. Geologists like Amos Frumkin have shown that the natural processes of evaporation, halite solubility, sediment loading, and seismic fracturing are sufficient to explain the Dead Sea’s unique salt formations. No supernatural event is required to account for these striking natural structures.

The famous “Lot’s Wife” near the Dead Sea is not a miraculous remnant but a naturally sculpted salt formation, shaped over millennia by erosion and halite creep.

Archaeological and Textual Mismatches

The identification of Tall el-Hammam as biblical Sodom is not accepted by most archaeologists. Several key issues undermine the claim:

- Geographic discrepancies between Tall el-Hammam’s location and biblical descriptions

- Chronological mismatches between the site’s destruction and the timeline of Abrahamic narratives

- Lack of textual correlation beyond superficial similarities in setting or disaster themes

- Alternative sites such as Bab edh-Dhra and Numeira show stronger archaeological continuity and are closer to the traditional “Cities of the Plain” region

Even the “burned” layers at Tall el-Hammam can easily be explained by human warfare or large-scale fire, both common causes of ancient urban destruction.

No Pillar, No Impact

The Bible’s account of Sodom and Gomorrah—fire from heaven, brimstone raining down, a woman turned to salt is gripping and rhetorically powerful. But to date, no incontrovertible geological or mineralogic evidence supports the claim that Tall el-Hammam, or any other site, was destroyed by a cosmic impact or divine fire.

The foundational 2021 paper making that claim has been retracted. Subsequent peer-reviewed critiques, such as Jaret & Harris (2022), have shown that the supposed evidence does not meet scientific standards. And the famous salt pillars of the Dead Sea are natural formations shaped by time, not miracles.

In short: the story remains myth, not material fact. Until rigorous, replicable evidence emerges, we must treat “Sodom’s destruction” as ancient storytelling—moral metaphor rather than meteorite.

References:

- Bunch, T. E., LeCompte, M. A., Adedeji, A. V., Wittke, J. H., Burleigh, T. D., Hermes, R. E., Mooney, C., et al. (2021). A Tunguska sized airburst destroyed Tall el-Hammam, a Middle Bronze Age city in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea. Scientific Reports. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-97778-3

- Jaret, S. J., & Harris, R. S. (2022). No mineralogic or geochemical evidence of impact at Tall el-Hammam, a Middle Bronze Age city in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea. Scientific Reports. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-08216-x

- Retraction Note: A Tunguska sized airburst destroyed Tall el-Hammam… (2025, April). Scientific Reports. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-99265-5

- Frumkin, A., & Raz, E. (2001). Mount Sedom: The structure and evolution of a salt diapir in Israel. Journal of Structural Geology, 23(9), 1351–1363. DOI: 10.1016/S0191-8141(01)00012-0

- Gabai, R., Lyakhovsky, V., & Weinberger, R. (2009). Salt diapirism in the Dead Sea area: From formation to present-day evolution. Tectonophysics, 470(3-4), 236–247. DOI: 10.1016/j.tecto.2009.01.017

- Ben-Avraham, Z., Lazar, M., & Gat, J. R. (2002). The geology and formation of the Dead Sea rift basin and its salt deposits. Earth-Science Reviews, 58(1-2), 1–20. DOI: 10.1016/S0012-8252(01)00079-3

- Garfunkel, Z., & Ben-Avraham, Z. (1996). Tectonics of the Dead Sea Rift. Tectonophysics, 244(1–2), 1–15. DOI: 10.1016/0040-1951(94)00203-L

- Sharon, D., & Frumkin, A. (2000). Salt karst and diapiric evolution of the Mount Sedom diapir, Israel. Geomorphology, 35(1–2), 85–102. DOI: 10.1016/S0169-555X(00)00015-8