The Shroud of Turin is often claimed to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, miraculously bearing his image after the crucifixion. For centuries it has inspired devotion, controversy, and intense scientific scrutiny. But when the full body of evidence is examined—historical, chemical, and physical—the conclusion is clear: the Shroud is not authentic and does not date to the time of Jesus.

Radiocarbon Dating: Conclusively from 13th Century

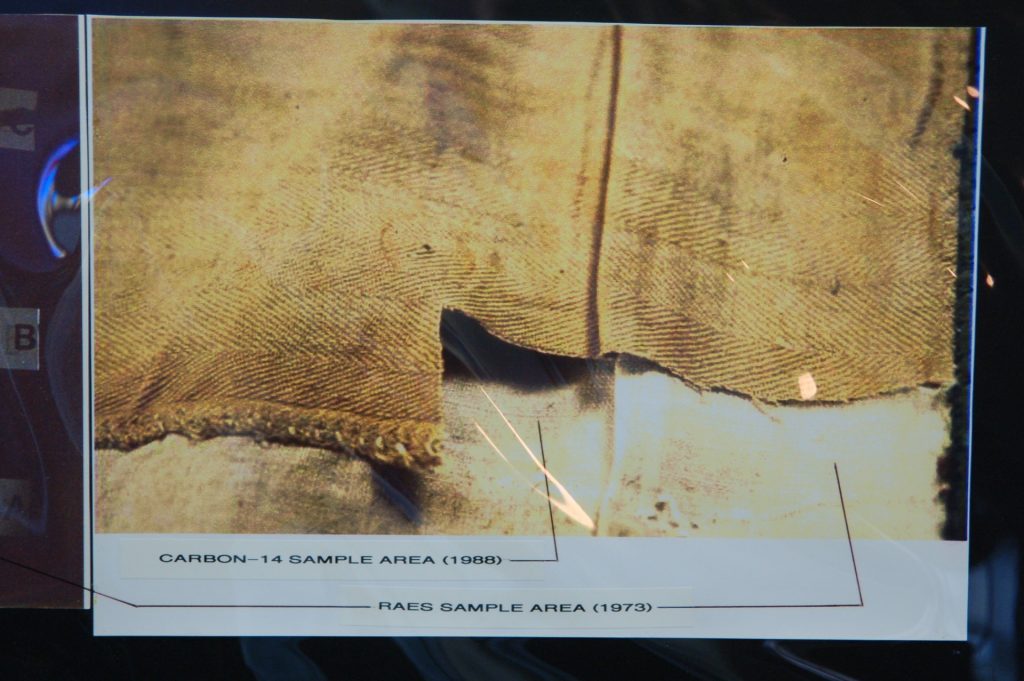

In 1988, the Shroud of Turin underwent the most direct and objective test available for determining its age: accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating. Small samples of the linen were independently analyzed by three internationally respected laboratories at the University of Oxford, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, and the University of Arizona. Each laboratory followed blind testing protocols and standard pretreatment procedures to remove potential contaminants before measurement.

Despite being conducted independently, all three laboratories reached essentially the same conclusion. When the results were combined and statistically analyzed, the linen was dated to between 1260 and 1390 AD with 95 percent confidence. The consistency across laboratories is significant, as radiocarbon dating errors or contamination effects typically produce divergent results rather than tight convergence.

This timeframe places the Shroud squarely in the medieval period and aligns precisely with its first undisputed historical appearance in 14th-century France.

Claims that contamination, fire damage, or microbial growth could shift the date by over a millennium are not supported by chemistry. Such effects would need to alter more than half the measurable carbon-14 content, a scale of interference that would be obvious and has never been demonstrated. Radiocarbon dating remains the strongest single piece of evidence against authenticity and has never been overturned.

The linen dates to between 1260 and 1390 AD (95% confidence).

Image Formation: Indicates Fabricated

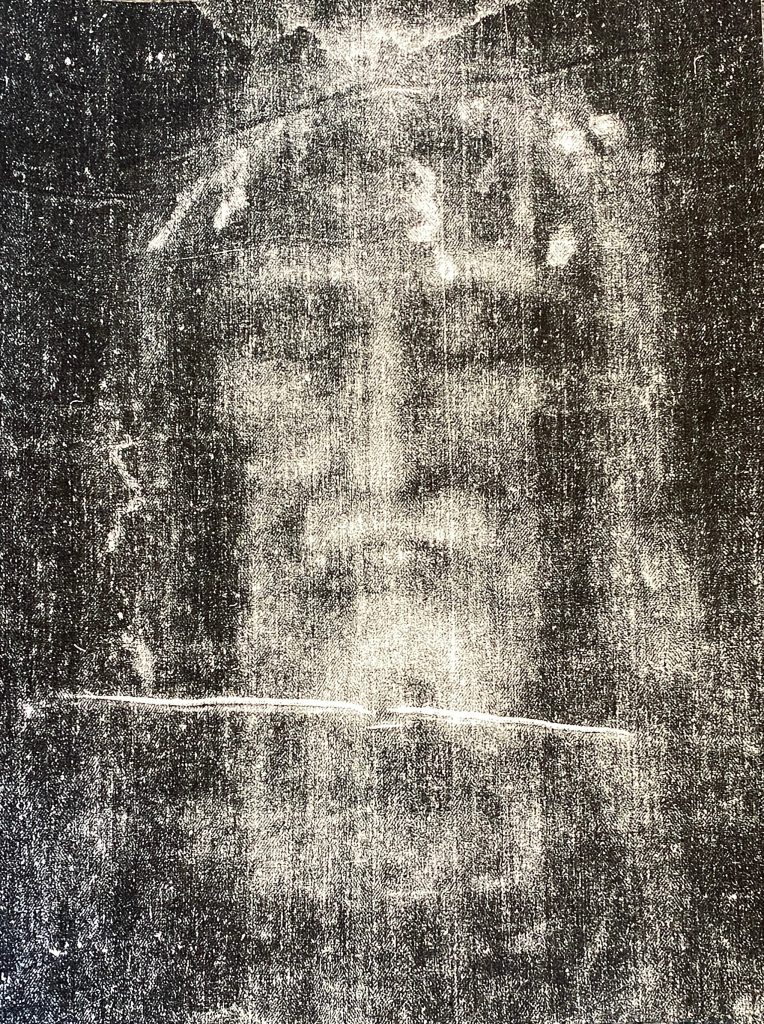

The image on the Shroud is unusual—superficial, monochromatic, and without visible brush strokes—but “unusual” does not mean miraculous.

Key observations:

- The image affects only the outermost fibers of the linen and does not penetrate deeper.

- It contains no bodily fluids.

- No natural decomposition process can produce this kind of selective surface image.

Several medieval techniques could explain the image without modern technology:

- Bas-relief rubbing: pressing cloth over a shallow sculpted figure to transfer a faint image.

- Chemical reactions: treating linen with substances that cause surface discoloration.

- Low-heat methods: applying heat or steam to lightly scorch the surface.

All these methods were possible in the Middle Ages. The Shroud’s image is unusual, but everything about it is consistent with a carefully created medieval artifact rather than a miraculous imprint.

The “Photographic Negative” and 3D Claims

The Shroud is often described as a photographic negative, but this is misleading. A true photographic negative requires light-sensitive chemicals and an optical exposure process, neither of which are present on the cloth. The Shroud contains no silver salts or evidence of light-based image formation. Instead, the image is a superficial discoloration of the linen fibers. Its negative-like appearance is the result of tonal inversion, which can occur naturally through shading, contact, or surface chemical effects and does not require any knowledge of photography.

Claims that the Shroud uniquely encodes three-dimensional information are also exaggerated. While image brightness loosely correlates with cloth-to-body distance, the relationship is rough and inconsistent. The effect works only in some areas and breaks down in others, which indicates a general contact or diffusion process rather than precise depth encoding. Similar 3D-like results can be produced from non-miraculous images using simple techniques.

Importantly, the STURP team did not conclude that the image was supernatural. They stated only that the exact image-formation process was unknown at the time, leaving open the possibility of natural or artistic explanations.

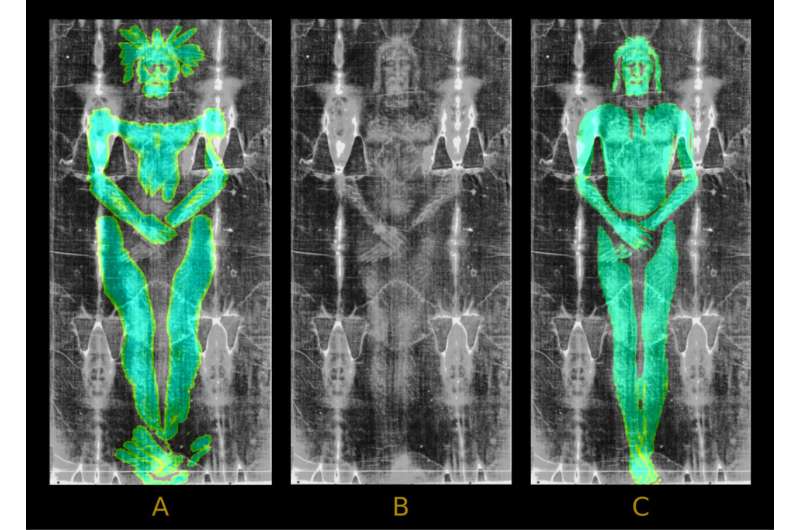

Shroud of Turin image matches low-relief statue—not human body, 3D modeling study finds

Anatomy and Crucifixion Details

Proponents frequently cite anatomical details such as nail placement near the wrists rather than the palms. However:

- Medieval anatomists understood that palms alone could not bear body weight

- Crucifixion depictions varied widely throughout medieval art

- The precise nail location on the Shroud is ambiguous

- Roman crucifixion practices were not standardized

These details are consistent with medieval knowledge and do not uniquely indicate a first-century origin.

Pollen and Provenance Claims

Max Frei’s pollen analysis has been widely cited to argue for a Middle Eastern origin. However, his work suffers from serious methodological flaws, including poor chain of custody, lack of reproducibility, and disputed identifications. Cross-contamination from centuries of handling and relic veneration provides a far more parsimonious explanation.

As a result, Frei’s pollen evidence is generally regarded as unreliable in modern scholarship.

Chemical Evidence and Pigments

Microscopic and spectroscopic studies have identified iron oxide particles and pigment-like residues on image fibers. While this does not conclusively prove painting, it directly undermines claims that the image resulted solely from natural bodily processes. No verified biological mechanism produces a high-resolution, superficial linen image without chemical residue.

Early Clerical Skepticism: Oresme and d’Arcis

Skepticism toward the object believed to be the Shroud of Turin did not originate with modern science—it emerged within the medieval Church itself.

The 14th-century theologian and philosopher Nicole Oresme explicitly denounced what he described as a “clear” and “patent” forgery produced by clergy to solicit donations from the faithful [1]. Oresme condemned the practice of manufacturing relics and deceptive images to manipulate popular devotion, indicating that such fraudulent objects were already recognized and criticized in his time.

This denunciation predates the well-known 1389 memorandum by Pierre d’Arcis, Bishop of Troyes, who likewise condemned the Shroud as an artwork created by an artist and falsely presented as Christ’s burial cloth. D’Arcis informed Pope Clement VII that the object was known to be man-made and that its creator had admitted the deception.

Together, these documents demonstrate that skepticism about the Shroud’s authenticity existed at its very emergence, including among educated clergy.

Medieval manuscript illustration of Nicole Oresme (bishop denouncing as forgery)

Historical Silence

Beyond these denunciations, the broader historical record is strikingly silent. There are no references to such a burial cloth in the first thirteen centuries of Christianity. No Church Father, historian, theologian, or pilgrim describes an object resembling the Shroud prior to the mid-14th century.

For a relic of such theological and devotional importance, this absence is decisive.

The Verdict

The Shroud of Turin is a fascinating medieval artifact—culturally powerful, historically intriguing, and scientifically unusual. But it is not the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth.

The evidence overwhelmingly supports a medieval origin:

- Radiocarbon dating places it between 1260 and 1390 AD

- Its historical appearance begins in 14th-century France

- The image can be explained without invoking miracles

- Clerical authorities contemporaneous with its debut denounced it as a forgery

Science does not threaten faith, and faith does not require fabricated relics. The Shroud belongs to medieval history, not the resurrection narrative.

Conclusion:

The Shroud of Turin was created between 1260 and 1390 AD, not around 30 AD.

References

- Nicole Oresme, Tractatus de configurationibus qualitatum et motuum and related theological writings condemning fraudulent relics (14th century)

- Pierre d’Arcis, Memorandum to Pope Clement VII (1389)

- Damon et al., Radiocarbon, 1989 – “Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin”

- Hedges, Nature, 1989 – Commentary on AMS dating

- STURP Final Report, 1981

- Nickell, Joe – Inquest on the Shroud of Turin

- Garlaschelli, Luigi – Experimental reproduction studies

- Adler, Alan – Chemical analyses of image fibers

- Rogers, Raymond – Textile and chemical critiques

- The Shroud of Turin: An Overview of the Archaeological Scientific Studies

https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7248/5/1/8 - Shroud of Turin image matches low-relief statue

https://phys.org/news/2025-08-shroud-turin-image-relief-statue.html