A Philosopher Challenges the Empire

In the 2nd century CE, the Roman Empire was a vast and diverse world, home to a wide range of religious traditions. Temples to gods lined the streets, rituals were woven into daily life, and the state demanded loyalty not just to the emperor but to the divine forces that supposedly upheld Rome’s power.

Yet, within this world, a new group was emerging—one that refused to participate in the traditional religious practices of the empire. These people, calling themselves Christians, followed an unusual belief system that rejected the gods of Rome.

Most Roman officials saw them as strange at best and dangerous at worst. They weren’t known for stirring up rebellion, but their refusal to acknowledge the gods was seen as an act of defiance against Roman society itself.

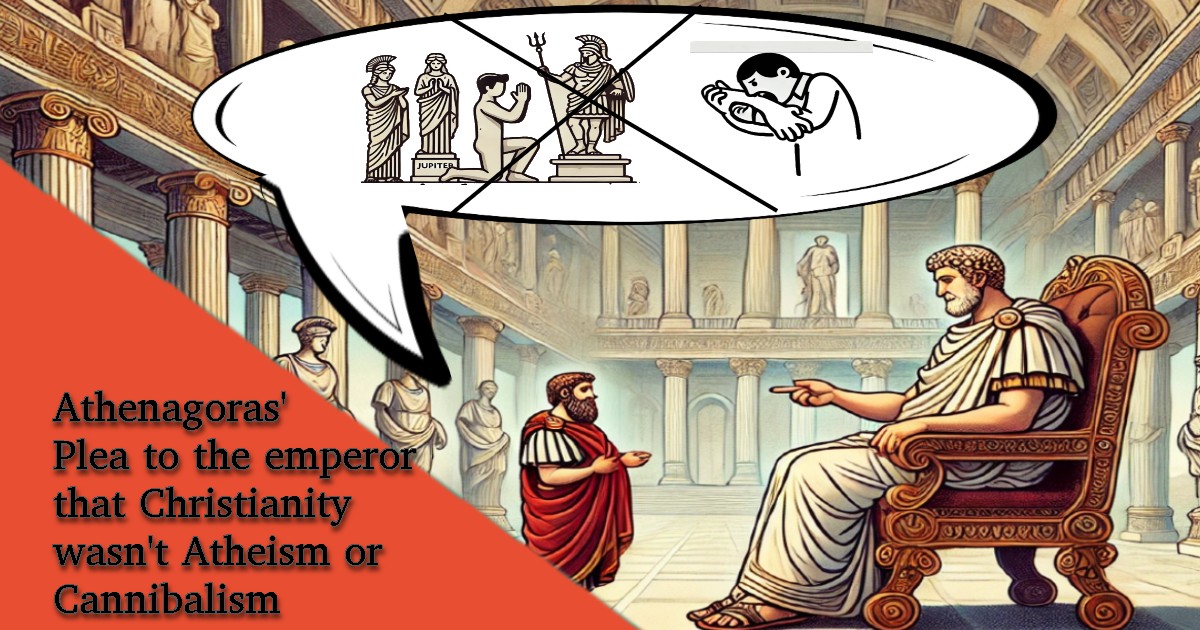

Enter Athenagoras of Athens, a philosopher who took an unconventional approach. Instead of distancing Christianity from controversy, he leaned into it—writing A Plea for the Christians, an argument so carefully crafted that it forced the empire to reconsider its stance.

Reframing the Debate: Athenagoras’ Strategy

Rather than appealing to religious authority, Athenagoras built his case around logic, justice, and morality—ideas that Roman intellectuals and rulers prided themselves on. He wasn’t just defending Christianity; he was making an argument that, if accepted, would challenge Rome’s assumptions about religion and governance.

Justice Demands a Fair Trial

Athenagoras opens with a simple yet cutting observation: Christians are being judged without evidence, simply because of their name.

In a society that prided itself on law and order, this was a serious charge. Rome had a legal system designed to ensure that people were punished for what they did, not for who they were. By pointing this out, Athenagoras forced a contradiction—if Rome was truly just, why were these people being judged without due process?

The argument wasn’t about proving Christianity right. It was about forcing the empire to follow its own rules.

Who Are the Real Atheists?

One of the strangest accusations against Christians was that they were atheists—not because they rejected all gods, but because they refused to worship Rome’s.

Athenagoras flips this on its head. He argues that the real problem isn’t whether people believe in gods, but what they believe about them. If people worship idols—statues crafted by human hands—are they truly engaging with anything divine, or just engaging in elaborate traditions?

By posing the question this way, Athenagoras wasn’t just defending Christianity—he was poking at the entire foundation of religious belief. How do people know which gods are real? How does tradition become truth? These were dangerous questions in an empire built on the idea that its gods protected its rule.

Christians Are Not a Threat to Society

Beyond philosophy, Athenagoras makes a practical argument: Christians, regardless of their beliefs, are model citizens.

- They follow the law.

- They don’t cause uprisings.

- They encourage ethical behavior.

If Rome’s goal was a stable and orderly society, then persecuting people who were law-abiding made no sense. Athenagoras wasn’t asking the emperor to embrace Christianity—he was simply pointing out that punishing peaceful people was a waste of effort.

Athenagoras’ Impact: A Shift in the Conversation

Athenagoras’ Plea is significant not because it immediately changed Roman policy (it didn’t) but because it reframed how Christianity was debated.

Moving the Debate Away from Religion

Rather than focusing on theology, Athenagoras shifted the conversation to law, reason, and morality—areas where even skeptics could find common ground.

Questioning Religious Assumptions

By subtly challenging how people thought about gods, traditions, and rituals, Athenagoras added to a growing undercurrent of philosophical skepticism about religious practices that had existed for centuries.

Setting a Precedent for Legal Protection

Though his Plea didn’t end Christian persecution, it contributed to a longer trend of legal arguments that would eventually lead to religious toleration in the empire. If belief alone was not a crime, then over time, Rome would have to rethink its stance on minority religions altogether.

Final Verdict: A Clever Rhetorical Strike

Athenagoras didn’t win an immediate victory, but he didn’t need to. His letter was a seed planted in the cracks of Rome’s religious and legal foundations—one that would, over time, help shift how society viewed belief, justice, and tradition.

He wasn’t just defending Christianity. He was forcing the empire to take a hard look at itself—and that was perhaps the boldest move of all.

References

- Athenagoras of Athens, A Plea for the Christians. Translated by B.P. Pratten. In Ante-Nicene Fathers, Volume 2. Edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994.

- Barnes, Timothy D. Early Christian Hagiography and Roman History. Mohr Siebeck, 2010.

- Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds of Early Christianity. 3rd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003.

- Grant, Robert M. Greek Apologists of the Second Century. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1988.

- Wilken, Robert Louis. The Christians as the Romans Saw Them. 2nd ed. Yale University Press, 2003.

- Young, Frances M. From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and Its Background. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2010.