For many Christians, hell is imagined as a blazing underworld a vast lake of fire and brimstone where the wicked scream under endless torture. Demons lurk in the flames, dragging souls into pits, while molten rivers crackle beneath a sky choked with smoke. It’s a place preached with certainty, illustrated in centuries of art, and feared with a visceral, cinematic intensity.

But when we go back to the Scriptures themselves, something surprising appears:

The Bible does not describe the hell we imagine today.

Not the Old Testament.

Not Jesus.

Not Paul.

The modern concept of hell — eternal conscious torment — took shape centuries after the biblical writings through cultural exchange, evolving theology, and imaginative literature.

The Old Testament Never Describes Hell

The Hebrew Bible does not describe hell as a fiery realm of eternal punishment. Instead, it uses one primary word for the realm of the dead: שְׁאוֹל (Sheol).

Sheol is:

- A silent, shadowy place where life has departed;

- The common destination of all people, both righteous and wicked;

- Not a place of torment, judgment, or reward;

- Often synonymous with “the grave”, the place where the body rests.

In Sheol, there is no fire, no demons, no torture, and no eternal punishment. It is a neutral, often bleak concept of the afterlife: a realm of inactivity and separation from the living, but not necessarily suffering.

Examples of Sheol in the Hebrew Bible

“All his sons and all his daughters sought to comfort him, but he refused to be comforted. He said, ‘No, I shall go down to Sheol to my son mourning.’ Thus his father wept for him.”

Here, Jacob speaks of Sheol simply as the place where the dead go — there is no suggestion of punishment or fire.

- Psalm 16:10

“For you will not abandon my soul to Sheol, or let your holy one see corruption.”

Some translations render Sheol as “hell,” but the original Hebrew conveys the grave or the abode of the dead, not a fiery hell.

“Before I go—and I shall not return—to the land of darkness and the shadow of death, to a land as dark as darkness itself, as shadow of death, without order, and where light is like darkness.”

Job describes Sheol as a gloomy, inescapable underworld, a place devoid of clarity and vitality, not a place of fiery punishment.

“Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with your might, for there is no work or planning or knowledge or wisdom in Sheol, to which you are going.”

Here, Sheol is portrayed as a realm of inactivity, where neither reward nor suffering continues — emphasizing its neutrality.

Why Translations Misled Readers

Many English Bibles, especially older translations like the King James Version, translate Sheol as “hell.” This translation was not a reflection of the original Hebrew meaning. Instead, translators often projected later theological ideas — fiery punishment, eternal torment — onto the text.

The original concept of Sheol reflects ancient Israelite beliefs about death: all the dead descend to the same shadowy realm, awaiting God’s ultimate judgment or resurrection. It was not a moralized place of torment designed to punish sinners.

Jesus Did Not Teach Eternal Torment

While Jesus frequently spoke about judgment and consequences, His teachings in the Gospels do not describe eternal, conscious torment. Instead, Jesus’ warnings are about destruction, removal, or annihilation rather than unending suffering.

Resurrection for the Righteous

Jesus promised resurrection and life to the faithful. For example:

- John 5:28–29 – “Do not marvel at this; for the hour is coming, in which all who are in the tombs will hear His voice, and will come forth; those who have done good, to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil, to the resurrection of judgment.”

Here, the righteous are promised life, while the wicked face judgment — the focus is on outcome, not eternal torment.

Destruction for the Wicked

Jesus often uses fire and cutting metaphors to describe the fate of the unfaithful:

- Matthew 3:10 – “Even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.”

- Matthew 7:19 – “Every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire.”

- Matthew 13:40–42 – “As the weeds are collected and burned with fire, so it will be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send His angels, and they will collect out of His kingdom all causes of sin and all law-breakers, and they will throw them into the fiery furnace, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

In all of these passages, fire is a metaphor for destruction, not eternal conscious suffering. The emphasis is on the complete removal or annihilation of the wicked, not preserving them in perpetual agony.

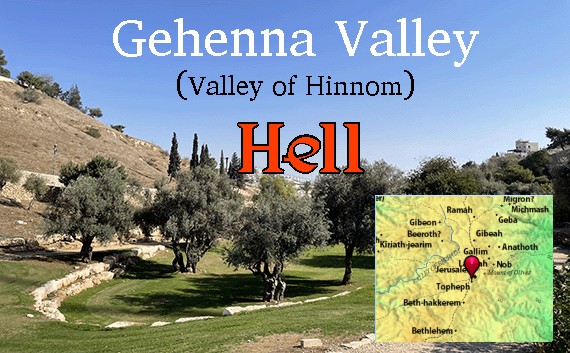

Gehenna: A Physical Reference

Jesus occasionally uses the term Gehenna (Greek: γέεννα) — traditionally translated as “hell.” Gehenna was:

- A real valley outside Jerusalem (Valley of Hinnom)

- Historically associated with child sacrifice and idolatry

- Later used as a site for burning refuse and corpses

Example:

- Mark 9:43 – “And if your hand causes you to sin, cut it off. It is better for you to enter life crippled than with two hands to go to Gehenna, to the unquenchable fire.”

- Matthew 5:22 – “But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother shall be guilty before the court; and whoever says, ‘You fool!’ shall be liable to hell [Gehenna] of fire.”

In these passages, Gehenna functions as a vivid metaphor rooted in a physical location familiar to Jesus’ audience, warning of severe consequences for sin. It is not described as a literal, underground chamber of eternal torment. The imagery is moral and rhetorical, meant to convey the seriousness of sin and the finality of judgment.

Fire as Final Destruction

Across Jesus’ parables:

- Weeds are burned (Matthew 13:40)

- Trees are cut down and thrown into the fire (Matthew 7:19)

- Chaff is consumed (Matthew 3:12)

Fire represents ultimate destruction. It terminates, it purifies, it removes, but it does not preserve the wicked in unending suffering. Jesus’ audience would have understood this metaphor as punishment ending in annihilation, not eternal torture.

Paul Never Mentions Hell

Paul, the earliest Christian writer, teaches clearly about:

- Christ’s return

- Judgment

- Resurrection

- Eternal life

But Paul never describes:

- A fiery hell

- Demons torturing souls

- Eternal conscious torment

Instead he speaks of the wicked facing destruction — the complete end of life, not its eternal continuation in suffering.

Where Did the Fiery Hell Come From?

If the Old Testament doesn’t describe it…

If Jesus doesn’t teach it…

If Paul doesn’t mention it…

How did Christians end up with the blazing, monstrous hell of popular imagination?

The answer lies in centuries of cultural exchange, theological adaptation, and literary creativity that transformed early Jewish and Christian ideas into something far larger and far more terrifying.

Below is the expanded explanation.

Jewish Thought Meets the Ancient Mediterranean World

Ancient Judaism did not develop in isolation. Over centuries, Jewish communities lived under and interacted with powerful empires—Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, and Roman—each with rich and elaborate afterlife traditions. As these cultures intersected with Jewish thought, ideas about death, judgment, and the fate of souls mixed, clashed, and evolved.

Influences came in many forms:

- Greek Hades: In Greek mythology, Hades was the shadowy underworld where all souls went after death. It was divided into regions for the righteous and the wicked, including the Elysian Fields for heroes and the virtuous, and the gloomy Asphodel Meadows for ordinary souls. The Greeks also imagined spirits enduring punishment or torment in proportion to their earthly deeds. Hades presented a moralized afterlife that distinguished between the fates of different souls—a concept that resonated with emerging Jewish ideas about reward and judgment.

- Tartarus: A deeper and darker aspect of the Greek underworld, Tartarus was reserved for divine rebels and the most egregious offenders. Titans defeated by Zeus were imprisoned there, and it was often depicted as a place of eternal punishment and unending suffering. Tartarus introduced the notion of a cosmic justice enforced over an indefinite or eternal duration, a concept that would echo in some Jewish and later Christian imaginings of ultimate judgment.

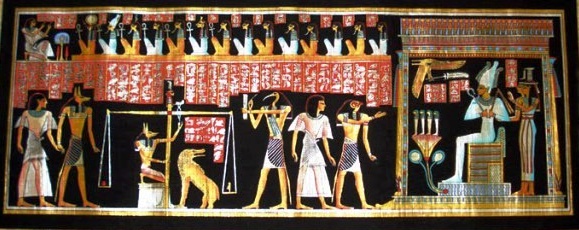

- Egyptian judgment scenes: These emphasized moral evaluation after death, with rituals like the weighing of hearts against Ma’at’s feather, lakes of fire, and torment for the wicked, reinforcing ideas of divine justice and postmortem consequence.

- Persian (Zoroastrian) dualism: This worldview framed life as a cosmic struggle between good and evil, with souls purified or punished after death according to their alignment. It contributed to Jewish thinking about moral accountability and the fate of the wicked.

These ideas were not simply copied wholesale. Instead, they interacted with Jewish prophetic and apocalyptic traditions, contributing to a richer and more nuanced imagination of the future, the afterlife, and divine justice.

Jewish Apocalypticism Reframed Death

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great, Hellenistic culture profoundly influenced the Near East, including Jewish thought. In this environment, Jewish apocalyptic writers—such as those responsible for Daniel, the Book of Enoch, and other intertestamental texts—began to develop vivid, symbolic visions of the afterlife and cosmic order.

Central themes included:

- Cosmic battles: Apocalyptic texts depicted struggles between divine and demonic forces, reflecting both moral and cosmic conflict. These battles often mirrored human history, emphasizing the eventual triumph of God and the punishment of the wicked.

- Angelic and demonic realms: Texts like 1 Enoch describe elaborate hierarchies of angels, including watchers who rebelled against God and were imprisoned or punished. This narrative introduced the idea that evil in the world has supernatural origins and that celestial justice is enacted alongside human history.

- Future judgment: Apocalyptic literature emphasized that God would ultimately judge both humanity and spiritual beings. In Enoch, the fallen angels (Watchers) are bound in chains, awaiting the final judgment, while humans are assessed according to their deeds, foreshadowing later eschatological ideas.

- Heavenly journeys: Figures such as Enoch himself are shown being taken on guided tours through the heavens, witnessing the workings of divine justice, the organization of the cosmos, and the fate of souls. These journeys provided a narrative framework for imagining what happens after death beyond the traditional realm of Sheol.

While Sheol remained part of the vocabulary—representing the shadowy abode of the dead—new imagery emerged: fiery rivers, angelic prisons, and scenes of divine retribution. The Book of Enoch, in particular, presents a complex afterlife where punishment is not only for humans but also for rebellious celestial beings, introducing the notion of a more moralized and structured system of justice.

Importantly, these visions were not yet “hell” in the later Christian sense. They were symbolic, visionary, and intended to convey moral and cosmic truths rather than describe a literal place of eternal torment. The emphasis was on divine justice, cosmic order, and the eventual restoration of righteousness, often connected to the unfolding of history and the vindication of the faithful on earth.

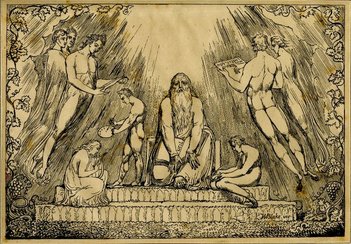

Hell Imagery Transformation through the updating story of Enoch

The story of Enoch illustrates how hell imagery evolved over time, gradually transforming from vague notions of the underworld into a detailed vision of punishment, darkness, and angelic confinement as successive versions of the text were updated.

The Book of the Watchers (c. 300–200 BCE)

- 1 Enoch 10:4–6 – Azazel is bound and cast into the desert of Dudael, a place of confinement.

- 1 Enoch 15:8–10 – The Watchers are punished in dark pits, chained and awaiting judgment.

- 1 Enoch 18:10–16 – Sheol described as a place of darkness and chains for the wicked.

The Animal Apocalypse / Book of Dream Visions (c. 160 BCE)

- 1 Enoch 90:20–26 – The unrighteous are punished with chains, fire, and pits, symbolic of ultimate justice.

The Book of Parables / Similitudes (c. 100 BCE)

- 1 Enoch 46:1–3 – The “Son of Man” comes to judge sinners, who are cast into fire and punishment.

- 1 Enoch 48:4–6 – Wicked kings are thrown into a fiery abyss, “where their worm does not die and fire is not quenched.”

The Epistle of Enoch (c. 100–50 BCE)

- 1 Enoch 102:7–8 – Wicked “consumed in unquenchable fire; their souls delivered into darkness.”

- 1 Enoch 104:2–5 – Sinners are cast into the abyss, from which there is no return.

- Subterranean confinement for fallen angels.

- Fiery punishment for the wicked.

- Darkness, chains, and pits.

- Often final destruction (not necessarily eternal conscious torment).

Enoch is not included in most Bibles because it was never part of the Hebrew canon; Jewish authorities excluded it from the Tanakh. Although some early Christians—particularly in the Ethiopian Church and a few Church Fathers—used it, the majority of Greek, Latin, and Hebrew traditions did not. Its apocalyptic and pseudepigraphal nature, claiming authorship by Enoch, Noah’s great-grandfather, while actually being composed centuries later, led it to be regarded as non-inspired. The text’s unusual cosmology, angels, and visionary material did not align fully with accepted Scripture, resulting in its exclusion from Protestant and most Catholic canons. An exception is the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which considers it canonical.

Early Christianity Reinterpreted Jesus

Jesus and the earliest Christians believed the Kingdom of God would arrive very soon, transforming the world and resurrecting the righteous. But as decades passed and Jesus’ return did not occur, Christian communities began interpreting His teachings spiritually rather than imminently.

Questions arose:

- If judgment didn’t happen on earth, would it happen after death?

- If the righteous live eternally, where do the wicked go?

- If Greco-Roman thinkers accepted differentiated afterlives, should Christians imagine something similar?

These questions gradually pulled Christian imagination toward more detailed, dualistic afterlife models.

The First Fully Developed Christian Hell: The Apocalypse of Peter – 2nd Century

One of the earliest detailed visions of a Christian hell appears in the Apocalypse of Peter, likely written in the 2nd century CE. Unlike the New Testament, which speaks of destruction and separation from God, this text presents a vivid, structured depiction of post-mortem punishment. Key features include:

- Punishment According to Sin: Sinners are punished in ways that reflect their earthly misdeeds.

- “And the sinners shall be in the fire… the gluttons are tormented with hunger, the drunkards with thirst…” (Apocalypse of Peter, 2.1–2)

- Lakes of Fire: The text describes fiery regions where souls suffer.

- “And there was a river of fire… and they were burned in the fire forever.” (Apocalypse of Peter, 6.2–3)

- Worms: Insects torment the wicked, reminiscent of later imagery in Christian literature.

- “And worms came out of their bodies, and they were eaten alive in the fire.” (Apocalypse of Peter, 8.3)

- Torments Tailored to Moral Failings: Each sinner experiences punishment specific to the sins they committed in life.

- “The adulterers are cast into an eternal furnace, and the liars are bound and their tongues cut out.” (Apocalypse of Peter, 9.4)

This text represents the first appearance of a “structured” hell in Christian thought—complete with sin-specific punishments and eternal torment—centuries after Jesus’ ministry, and long after Paul and the earliest Gospel traditions, which do not describe such a place.

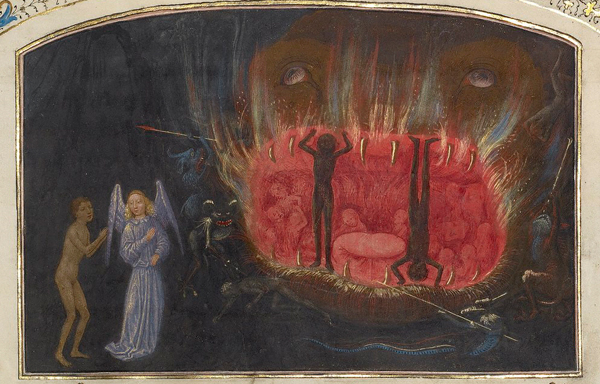

The Medieval Imagination Solidified Hell

As centuries passed, hell expanded dramatically:

- Preachers used terrifying hell imagery to call for repentance.

- Mystics described visionary journeys through the afterlife.

- Artists painted demons, flames, and torture.

- Medieval plays dramatized hell as both comedic and horrific.

By this time, hell had become a full cultural ecosystem — a place of torment far more detailed than anything found in Scripture.

Dante Gave Hell Its Final Form

In the 14th century, Dante Alighieri’s Inferno created the most influential depiction of hell in Western history:

- Nine circles

- Demons

- Ice, fire, storms, pits

- Punishments matched to sins

- A moral, political, and theological structure

Dante’s poem became the blueprint for the Christian imagination. His vision was not biblical, but literary — yet it shaped preaching, art, theology, and culture more deeply than any biblical passage ever did.

The modern Christian hell owes more to Dante than to Moses, Jesus, Paul, or even John.

References

- Bailey, Lloyd R. (1986) — “Gehenna: The Topography of Hell,” Biblical Archaeologist 49: 189–200

- Barclay, William I. (2001 [orig. 1969]) — The Gospel of Mark, The New Daily Study Bible, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press

- Beasley-Murray, G. R. (1986) — Jesus and the Kingdom of God, Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

- Bernstein, Alan E. (1993) — The Formation of Hell: Death and Retribution in the Ancient and Early Christian Worlds, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

- Block, Daniel I. (2004) — “The Old Testament on Hell,” in Christopher W. Morgan & Robert A. Peterson (eds.), Hell under Fire: Modern Scholarship Reinvents Eternal Punishment, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- Bolen, Todd. (2011) — “The Myth of the Burning Garbage Dump of Gehenna,” BiblePlaces.com Blog, April 7

- Burk, Denny. (2016) — “Eternal Conscious Torment,” in Preston Sprinkle (ed.), Four Views on Hell, 2nd edition, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- Carson, D. A. (1996) — Exegetical Fallacies, 2nd edition, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker

- Chan, Francis & Sprinkle, Preston M. (2011) — Erasing Hell: What God Said About Eternity and the Things We Made Up, Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook

- Crockett, William V. (1996) — “The Metaphorical View,” in William Crockett (ed.), Four Views on Hell, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- Demler, Ronnie & Tanksley Jr., William. (2016) — “Annihilation in 2 Thessalonians 1:9 (Part 2),” Rethinking Hell, December 5

- Dixon, Larry. (1992) — The Other Side of the Good News: Confronting the Contemporary Challenges to Jesus’ Teaching on Hell, Wheaton, IL: Victor Books

- Domeris, W. R. (1997) — “הֶ֫רֶג,” in William A. VanGemeren (ed.), New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis (NIDOTTE), vol. 1, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2020) — Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife, New York, NY: HarperOne

- Fudge, Edward W. (2011) — The Fire That Consumes: A Biblical and Historical Study of the Doctrine of Final Punishment, 3rd edition, Eugene, OR: Cascade

- France, Richard T. (2007) — The Gospel of Matthew, NICNT, Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans

- Grice, Peter. (2016) — “Annihilation in 2 Thessalonians 1:9 (Part 1),” Rethinking Hell, November 14

- Head, Peter M. (1997) — “The Duration of Divine Judgment in the New Testament,” in K. E. Brower & Mark W. Elliott (eds.), Eschatology in Bible & Theology: Evangelical Essays at the Dawn of a New Millennium, Downers Grove, IL: Inter-Varsity Press

- Instone-Brewer, David. (2015) — “Eternal Punishment in First-Century Jewish Thought,” in Christopher M. Date & Ron Highfield (eds.), A Consuming Passion: Essays on Hell and Immortality in Honor of Edward Fudge, Eugene, OR: Pickwick

- Jeremias, Joachim. (1964) — “γέεννα,” in Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, & Geoffrey W. Bromiley (eds.), Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 1, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans

- Levenson, Jon D. (2006) — Resurrection and the Restoration of Israel, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

- Morey, Robert A. (1984) — Death and the Afterlife, Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House

- Morgan, Christopher W. (2004) — “Biblical Theology: Three Pictures of Hell,” in Christopher W. Morgan & Robert A. Peterson (eds.), Hell under Fire, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- Papaioannou, Kim. (2013) — The Geography of Hell in the Teaching of Jesus, Eugene, OR: Pickwick

- Peoples, Glenn. (2012–2013) — “Worms and Fire: The Rabbis or Isaiah?” and “Matthew 10:28and dualism: Is the soul Immortal?” Rethinking Hell / Afterlife.co.nz

- Quarles, Charles L. (1997) — “The APO of 2 Thess 1:9and the Nature of Eternal Punishment,” WTJ 59: 201–211

- Quient, Nicholas R. (2015–2016) — “Paul and the Annihilation of Death,” in A Consuming Passion, and “Destruction from the Presence of the Lord: Paul’s Intertextual Use of the LXX in 2 Thess 1:9,” paper presented at Rethinking Hell Conference, London

- Reid, Daniel G. (2001) — “2 Thessalonians 1:9: ‘Separated from’ or ‘Destruction from’ the Presence of the Lord?” ETS Pauline Studies Group, Colorado Springs, CO

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. (1977–1984) — The Devil, multi-volume historical study, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

- Silva, Moisēs (ed.). (2014) — New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology and Exegesis, vols. 1–5, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- Stackhouse, John. (2016) — “Terminal Punishment,” in Preston Sprinkle (ed.), Four Views on Hell, 2nd edition, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

- Turner, Alice K. (1993) — The History of Hell, London: Routledge

- Wright, N. T. (2004) — Matthew for Everyone: Part 1, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press

- Wright, N. T. (2008) — Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church, New York, NY: HarperOne

- Dante Alighieri (1320) — The Divine Comedy, Italy