The cherished claim that Jesus was born of a virgin did not begin as a supernatural revelation. It began with a single mistranslated Hebrew word that snowballed into one of Christianity’s most defining doctrines. When the layers of language, tradition, and later theological editing are removed, the miracle starts looking less like divine truth and more like the product of linguistic confusion and an agenda to make Jesus fit the Hebrew Scriptures at any cost.

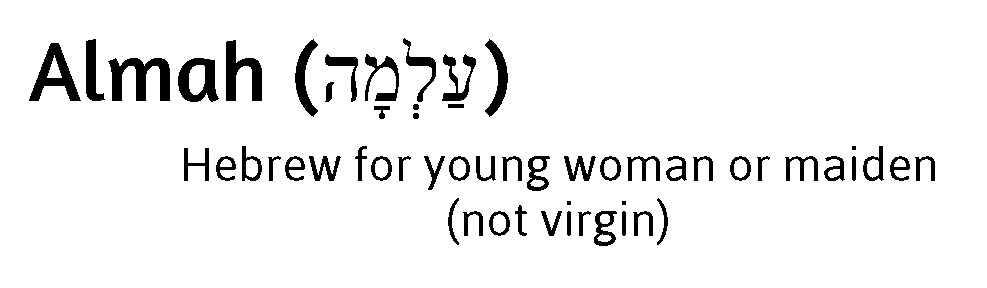

Everything turns on one Hebrew word in Isaiah 7 verse 14. The Hebrew uses the term almāh, which means a young woman of marriageable age. It never meant a miraculous virgin. Ancient Hebrew has a word for virgin, betulah, and Isaiah did not use it. The story around the verse makes this even clearer. Isaiah is speaking directly to King Ahaz in the eighth century BCE about a political crisis unfolding in his own lifetime. The promised child would be born in that generation and would serve as a sign that the two enemy kingdoms threatening Judah would soon fall. Nothing about the passage points to a distant messianic future and nothing involves a miraculous conception.

Hebrew Text — Isaiah 7:14

Source: Masoretic Text (JPS Tanakh / Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia)

הִנֵּה הָ‘עַלְמָה’ הָרָה וְיֹלֶדֶת בֵּן וְקָרָאת שְׁמוֹ עִמָּנוּ אֵל

Phonetic: Hinneh ha-almāh hā-rāh ve-yoledet ben ve-qāra’ shemo Immanu’el

Translation (literal)

Behold, the young woman is pregnant and is bearing a son, and she shall call his name Immanuel.

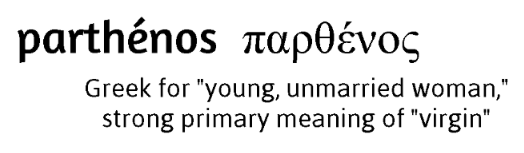

Centuries later, when Jewish scholars translated the Hebrew Bible into Greek in what became known as the Septuagint, they selected the Greek term parthenos for almāh. Parthenos could mean virgin, but it could also simply mean young woman. That ambiguity created the opening that later Christian writers walked through. The Gospel of Matthew, written anonymously decades after Jesus’ death, quotes Isaiah from the Greek version, not the Hebrew. Reading parthenos as virgin, the author presents Jesus’ birth as a prophetic fulfillment even though the original Hebrew did not say virgin and did not refer to a future messiah.

Greek Text — Isaiah 7:14

Source: Septuagint (LXX, Rahlfs–Hanhart)

Ἰδοὺ ἡ παρθένος ἐν γαστρὶ ἕξει καὶ τέξεται υἱόν, καὶ καλέσεις τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ Ἐμμανουήλ

Phonetic: Idou hē parthénos en gastri héxei kai téxetai huion, kai kaléseis to onoma autou Emmanouēl

Translation (literal)

Behold, the virgin will conceive in the womb and will bear a son, and you shall call his name Emmanuel.

Matthew’s entire narrative shows the same pattern. The anonymous writer repeatedly inserts fulfillment formulas, claiming that various events in Jesus’ life happened to fulfill prophecies. Many of these so called prophecies are not predictions at all when read in Hebrew and in context. They were repurposed, reinterpreted, or pulled out of context to construct a theological biography that made Jesus fit the expectations of Jewish scripture. Isaiah 7 becomes part of this pattern. The child originally referenced was a contemporary child in Isaiah’s day, not a divine figure centuries later. But Matthew reshaped it into a miraculous event to strengthen Jesus’ messianic credentials.

This creative reinterpretation did more than proof text Christianity’s new figure of Jesus. It placed him alongside other ancient heroic figures who were also said to have miraculous births, such as Alexander the Great and Augustus. A virgin birth made Jesus competitive in a religious world saturated with divine conception legends. Luke later expanded the narrative with angelic announcements and poetic scenes, showing how the supernatural story grew with each retelling and distance from the original Hebrew context.

When the textual and historical evidence is examined, the miracle evaporates. Isaiah’s Hebrew text speaks of a normal young woman in the prophet’s own time. The virgin birth arises only after the passage is filtered through an imprecise Greek translation and then later woven into the anonymous gospel writers’ theological agenda. The result is a miracle crafted not from eyewitness memory but from interpretive creativity and a desire to tie Jesus tightly to the Hebrew Scriptures.

References

- Jewish Publication Society Hebrew Bible, JPS Tanakh 1985 Edition

- Septuagint, Rahlfs Hanhart Edition 2006

- Raymond E Brown, The Birth of the Messiah 1993

- Bart D Ehrman, Jesus Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium 1999

- John J Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible 2004

- John Goldingay, Isaiah for Everyone 2015

- Joseph Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke 1981

- Geza Vermes, The Nativity History and Legend 2006