The Orphic Mysteries were an ancient, esoteric religious movement rooted in Greece, centered around the mythical figure Orpheus, the legendary poet, musician, and prophet who could charm gods and mortals alike with his lyre. Unlike other mystery cults, the Orphic tradition emphasized personal spiritual purification, the immortality of the soul, and the cycle of reincarnation (metempsychosis), offering initiates secret knowledge about life, death, and the afterlife.

Time Period of the Orphic Mysteries

- Origins:

- Likely emerged around the 6th century BCE, though its roots may stretch back to even earlier pre-Homeric religious traditions.

- Classical Period (5th–4th centuries BCE):

- Flourished alongside other Greek religious movements, influencing philosophical schools like Pythagoreanism and Platonism.

- Hellenistic Period (3rd–1st centuries BCE):

- Spread throughout the Mediterranean, evolving under the influence of Eastern mysticism and Hellenistic syncretism.

- Roman Period (1st century BCE–4th century CE):

- Continued to thrive, often blending with mystery cults like the Dionysian and Eleusinian Mysteries.

Evidence for the Orphic Mysteries

Despite their secretive nature, the Orphic Mysteries left behind a trail of literary, archaeological, epigraphic, and iconographic evidence.

Literary Sources

- Orphic Hymns (c. 3rd century BCE – 2nd century CE):

- A collection of devotional poems dedicated to various gods, particularly Dionysus, hinting at Orphic cosmology and ritual practices.

- Orphic Theogonies (fragments, 6th century BCE onward):

- Mythological texts describing the creation of the cosmos, including tales of Chronos (Time), Phanes (the primordial light), and the dismemberment of Dionysus.

- Plato’s Dialogues (4th century BCE):

- In works like the Phaedo, Republic, and Cratylus, Plato references Orphic beliefs about the soul’s immortality, purification, and the afterlife.

- Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca Historica (1st century BCE):

- Describes Orpheus as the founder of sacred rites, music, and religious laws, highlighting his influence on Greek spiritual life.

- An Orphic Timeline

- Pindar’s Odes (5th century BCE):

- Alludes to Orphic purification rites and esoteric teachings about the soul’s journey after death.

- Alludes to Orphic purification rites and esoteric teachings about the soul’s journey after death.

Archaeological Evidence

- Orphic Gold Tablets (Totenpässe, 4th–3rd centuries BCE):

- Thin gold leaves buried with the dead in graves across Italy, Greece, and Crete, inscribed with instructions for navigating the afterlife.

- These tablets reveal key Orphic doctrines:

- The soul’s divine origin.

- The cyclical nature of reincarnation.

- Ritual passwords to ensure safe passage through the underworld.

- Burial Sites with Orphic Symbolism:

- Graves featuring imagery of Dionysus, serpents (symbols of rebirth), and inscriptions referencing Orphic teachings.

Inscriptions and Epigraphy

- Funerary Inscriptions (4th century BCE–2nd century CE):

- Carved texts on tombstones reflecting Orphic beliefs about the afterlife, such as phrases like “I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven”—a common Orphic declaration of the soul’s divine heritage.

- Initiatory Inscriptions:

- Found in sanctuaries, these inscriptions sometimes reference purification rituals and the Orphic path to spiritual liberation.

Iconographic Evidence (Art and Imagery)

- Vase Paintings (5th–4th centuries BCE):

- Depict scenes from Orphic mythology, including Orpheus playing his lyre, Dionysian rituals, and symbols of life, death, and rebirth.

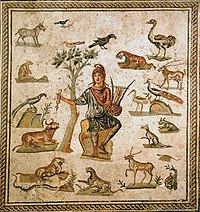

- Mosaics and Frescoes (Roman Period):

- Imagery featuring Orpheus as a mystical figure taming animals, representing his power over nature and the soul.

- Orphic Symbols:

- The egg (symbolizing the cosmos), serpents, and depictions of Phanes—the Orphic god of light and creation.

Philosophical and Esoteric Texts

- Neoplatonist Writings (3rd–5th centuries CE):

- Thinkers like Plotinus, Proclus, and Porphyry interpret Orphic myths as allegories for the soul’s journey toward enlightenment.

- Pythagorean Texts:

- Show deep influence from Orphic doctrines, particularly concerning reincarnation, asceticism, and the purification of the soul.

Comparative Evidence from Mystery Cults

- Dionysian and Eleusinian Mysteries:

- Shared rituals and myths suggest overlapping practices, especially concerning death, rebirth, and the divine spark within humanity.

- Orphic Influence on Early Christianity:

- Some scholars argue that Orphic concepts of the soul’s immortality and spiritual resurrection influenced early Christian thought, particularly in Gnostic texts.

Key Orphic Beliefs Revealed Through Evidence

- The Soul’s Divine Origin:

- Humans carry a divine spark, trapped in the material body as a form of punishment or trial.

- Reincarnation (Metempsychosis):

- The soul undergoes cycles of rebirth until it achieves purification and returns to the divine realm.

- Ritual Purification:

- Through initiation, ascetic practices, and secret rites, the soul can be cleansed of its earthly impurities.

- The Myth of Dionysus Zagreus:

- Dionysus, torn apart by the Titans and reborn, symbolizes the soul’s journey through death and regeneration—a central myth in Orphic cosmology.

Documents and References for the Orphic Mysteries

The Orphic Mysteries left behind a rich but fragmented collection of texts, inscriptions, and archaeological artifacts. These sources provide insight into Orphic beliefs about the soul, the afterlife, and the nature of the cosmos. Here’s a comprehensive list of the key documents and references:

Orphic Texts and Fragments

- Orphic Hymns (c. 3rd century BCE – 2nd century CE)

- A collection of 87 hymns dedicated to various gods, especially Dionysus. These hymns were likely used in ritual contexts, reflecting Orphic cosmology, theology, and rites of purification.

- Primary Source: Orphic Hymns, translated by Apostolos N. Athanassakis.

- Orphic Theogonies (fragments from 6th century BCE onward)

- Mythological texts detailing the creation of the universe. Key fragments include the Derveni Papyrus and later Neoplatonist references.

- Key figures: Chronos (Time), Phanes (the primordial deity), Nyx (Night), and Dionysus Zagreus.

- Derveni Papyrus (4th century BCE)

- The oldest surviving European manuscript, discovered in a tomb near Derveni, Greece.

- A philosophical commentary on an Orphic poem, discussing esoteric cosmology, ritual practices, and theological symbolism.

- Orphic Gold Tablets (Totenpässe, 4th–2nd centuries BCE)

- Thin gold leaves buried with the dead, inscribed with ritual instructions for navigating the afterlife.

- Found in burial sites across Greece, Southern Italy (Magna Graecia), and Crete.

Classical Literary References

- Plato’s Dialogues (4th century BCE)

- Phaedo, Republic, Cratylus, and Gorgias reference Orphic doctrines about the soul’s immortality, reincarnation, and purification.

- Plato discusses Orphic rites as part of the philosophical tradition of soul-care (psyche).

- Pindar’s Odes (5th century BCE)

- References to mystical purification and the soul’s journey after death, influenced by Orphic ideas.

- Euripides’ The Bacchae (5th century BCE)

- While primarily focused on Dionysian worship, it reflects Orphic themes of divine madness, death, and rebirth.

- Herodotus’ Histories (5th century BCE)

- Mentions Orphic rituals and practices in the context of Greek religious customs.

Archaeological Evidence

- Burial Inscriptions and Funerary Texts (4th century BCE–2nd century CE)

- Grave markers and tomb inscriptions referencing Orphic beliefs about the soul’s divine origin and the afterlife.

- Example inscriptions: “I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven, but my race is of Heaven alone.”

- Vase Paintings and Reliefs (5th–4th centuries BCE)

- Depictions of Orpheus, Dionysian rituals, and symbolic imagery associated with Orphic beliefs (e.g., serpents, the cosmic egg, and ivy crowns).

Later Philosophical and Theological Writings

- Neoplatonist Commentaries (3rd–5th centuries CE)

- Philosophers like Plotinus, Porphyry, Proclus, and Damascius discuss Orphic cosmology, mythology, and theology in allegorical terms.

- These works often reinterpret Orphic myths to fit Neoplatonic philosophical systems.

- Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca Historica (1st century BCE)

- Describes Orpheus as a foundational figure in Greek religion, elaborating on his role in establishing sacred rites.

- Clement of Alexandria’s Exhortation to the Greeks (2nd century CE)

- Critiques Orphic and other pagan mystery religions, inadvertently preserving valuable information about their doctrines.

Comparative References

- Pythagorean Texts

- Although not explicitly Orphic, many Pythagorean writings share themes of reincarnation, asceticism, and the soul’s purification, influenced by Orphic traditions.

- Early Christian Texts (1st–4th centuries CE)

- Church Fathers like Origen, Hippolytus, and Augustine reference Orphic teachings when critiquing pagan philosophies and mystery religions.

Modern Scholarly Collections

- Otto Kern’s Orphicorum Fragmenta (1922)

- The most comprehensive collection of Orphic fragments, widely used by scholars studying Orphic texts and rituals.

- Recent Scholarship:

- Radcliffe G. Edmonds III’s Redefining Ancient Orphism (2013): Challenges traditional interpretations of Orphic religion.

- Alberto Bernabé’s critical editions and translations: Provide updated analysis of Orphic fragments and inscriptions.

Commentary Analytical Sources:

An Orphic Timeline PDF

Rosicrucian Research Library. (2008). An Orphic timeline. Rosicrucian Digest, (1)

The Orphic Mysteries, though shrouded in secrecy, left a profound legacy in the form of sacred texts, burial artifacts, philosophical writings, and religious art. This mosaic of evidence reveals a rich spiritual tradition focused on self-discovery, transcendence, and the eternal quest to reunite the soul with the divine.